As discussed in our summary “Integrating Crop and Livestock Systems” post in February (link in photo at right), the long-held assumption was that hooves on crop land had negative effects to ultimate crop yield and soil health by way of:

- Increased Compaction

- Increased Runoff and Erosion

Our experience over 5+ years of grazing cattle on crop land has shown that, with the proper management, these issues can be completely avoided! Not only that, but we have found some additional positives for grazing cattle that are often not discussed. But first, let’s debunk the negatives.

Increased Compaction

The argument for why you would see increased compaction when cattle graze crop land is sound. Research has shown that the hoof off the average cow puts about 27 PSI to the ground when standing and can reach nearly 50 PSI while in motion. This unneeded pressure, when compared to having nothing touch the ground, must surely create compaction.

To a certain degree, we have seen a measurable change in compaction on land that has been grazed versus land that hasn’t. In 2019, our planter measured 1% loss of ground contact on non-grazed corn ground and 3.6% loss of ground contact on grazed land. Additionally, proper down force at each row was applied 98.7% of the time on non-grazed land and only 96.1% of the time on grazed land. These are signs of compaction, but are they signs of decreased yield?

Compaction Case

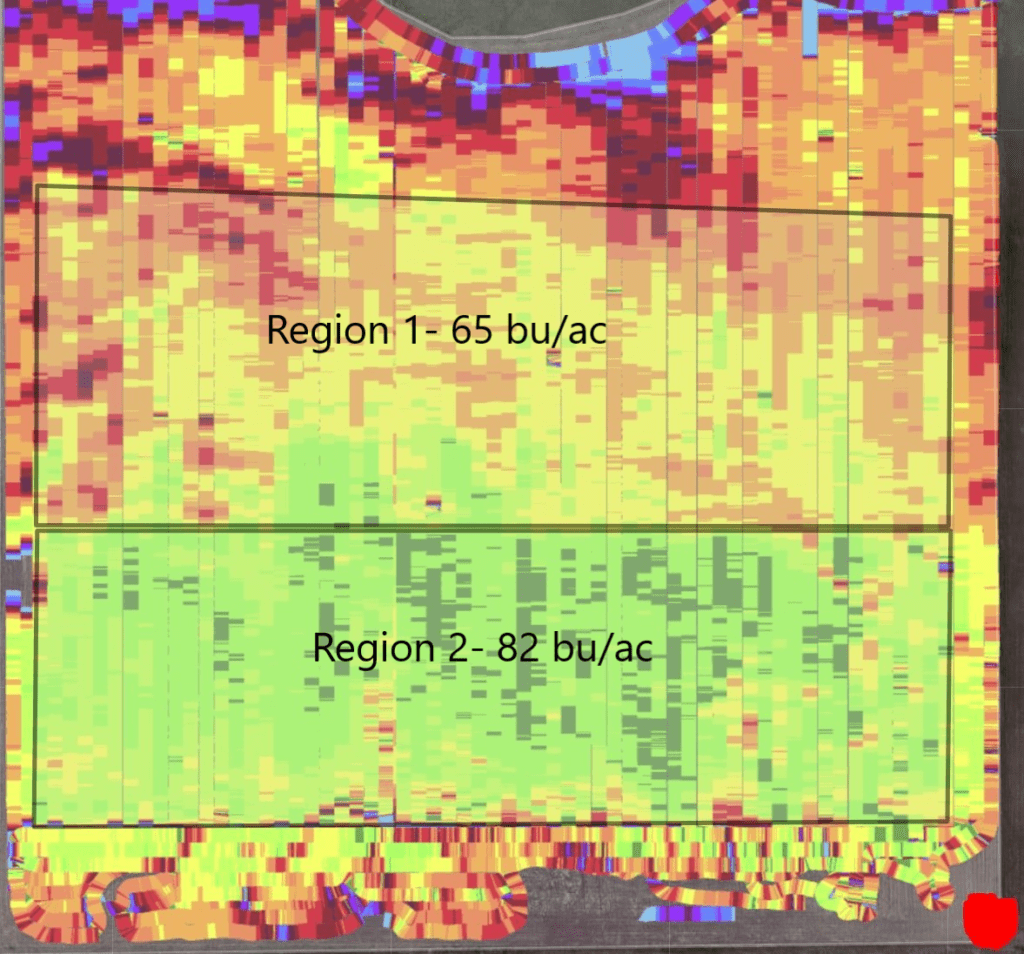

This image is a yield map of a winter wheat field harvested in 2018 after being grazed by 200 bulls for around 90 days during the winter of 2017-2018. The red dot on the bottom right corner of the image is the location of a watering facility. Its location is important, because it would indicate that areas closer to it would have received more cattle traffic, and therefore more compaction and decreased yield. As you can see in the image, the opposite is true. The region of the field closer to the watering facility had measurably higher yield.

Therefore, we see that even in areas with increased traffic, yield drag can be avoided with the proper management practices. These cattle grazed the land while it was frozen, helping reduce compaction. It is possible to avoid compaction while in-season grazing, as well. A necessary management practice in that scenario is to keep cattle off any crop land that is wet or recently received rain.

Increased Runoff and Erosion

As with increased compaction, the face value argument for increase erosion on crop land that has been grazed is sound. The cattle consume the residue necessary to hold the soil together, and heavy rain or snow melt will take topsoil and any soil nutrients away with it. This situation is possible, but with the correct management, can be totally avoided.

Take Half, Leave Half

One way to avoid increased erosion it to follow good grazing practices. Take for example this photo, taken after a grazing pass with a group of heifers in 2019. A good rule of thumb is to take half and leave half of whatever plant material is available in the field. The correct levels of residue left behind ensure adequate energy stored in the remains of the plant for strong regrowth, and the growing root keeps the soil together, even during strong rainfall events.

Runoff and Winter Grazing

The case with winter grazing is slightly different, as we are not concerned about regrowth, and are instead are concerned about consuming and recycling as much of the available plant residue as possible. While this means less residue on the surface, we cannot forget about what is going on below the soil. Look at the root mass of this cover crop regrowth after being grazed during the winter. Even though that plant may not have been alive during snow melt, its root mass still existed, giving good structure to the soil. It is also this root mass that ensure good regrowth after the winter, protecting the unplanted soil from heavy spring rains.

Improved Water Infiltration

Another erosion reducing aspect that would be surprising to those skeptical of grazing cattle on crop land is improved water infiltration. It would be reasonable to assume that crop land compacted by hooves and grazed off by cattle would not effectively move water through its soil profile. Not only have we seen that compaction can be non-existent (or at least not detrimental to yield) but we have also seen that the presence of a cover crop, grazed or not, improves water infiltration. The way this is measurable for us is an analysis of corn planting dates of fields both grazed and not razed by cattle over the fall/winter of the previous year. In 2019, a year with an unreasonably wet spring that caused planting problems across the corn belt, we were in the field 6 days earlier on land that had been grazed by cattle than land that hadn’t. The presence of cover crops and their root systems allowed water to flow freely down, and the hoof action of a grazing animals helps to mellow out and stir up the topsoil such that water can get to the root zone and down!

So, What about the Positives?

While it’s a good exercise to show that the potential negative effects of hooves on crop land can be avoided, proving that alone maybe doesn’t justify the practice to some. What we need to see are positive effects that we wouldn’t otherwise see without the presence of hooves. Certainly, earlier planting dates area measurable positive, but what about tangible changes in yield or soil nutrient levels? Tune in for our next blog post for our take on the positive soil health effects we have seen from grazing cattle on crop land!